This article is a part of my fieldwork at the Tehran’s Behesht-e Zahra cemetery from 2014-2015. I published another version of this idea in Persian in Iran in 2017. In the first version, I had a collaboration with Jabbar Rahmani, anthropologist, and this version I had a collaboration with Zohreh Bayatrizi, sociologist. The idea of these papers came to my mind during my fieldwork in the cemetery.

[…] Tehran’s current cemetery is called Behesht-e Zahra (literally, The Paradise of Zahra, named after Prophet Mohammad’s daughter) first opened on 314 ha of land in the southern outskirts of the city in 1970 in a bid to provide a permanent and centralized burial site for its rapidly growing population. Up until then local residents had buried their dead in one of the several graveyards within the city (Behesht-e Zahra, undated).1 Although at first the cemetery struggled to find a taker for its first grave, due to its distance from the city, lack of high-speed public transit, and scarcity of car ownership at the time, it now has over 1.5 million graves and has expanded to incorporate an additional 110 ha in 1997 and another 160 ha in 2009. The eight year war with Iraq (1980–1988) created a sharp rise in burials for the fallen soldiers who were buried in a dedicated parcel and gave the cemetery additional political and sentimental significance. A massive development project began in 1989 with the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic, which led to the creation of a mausoleum and a major cultural, religious and tourist complex adjacent to the cemetery. With the expansion of car ownership and the extension of the subway line, the cemetery currently accommodates on average about 15,000 visitors per day with a major spike on the weekends. There are 164 lots in the cemetery, 18 of which are dedicated to the ‘martyrs’ and their parents, 3 to journalists, cultural and entertainment figures, and one to organ donors. These lots are located in prime spots in the older part of the cemetery, which are easier to access and highly sought after. The vast majority of the remaining lots are divided into one-, two-, and three-tier graves. One-tier graves in the new parts of the cemetery can be obtained free of charge. Multi-tired graves and graves in more desirable plots are up for sale.

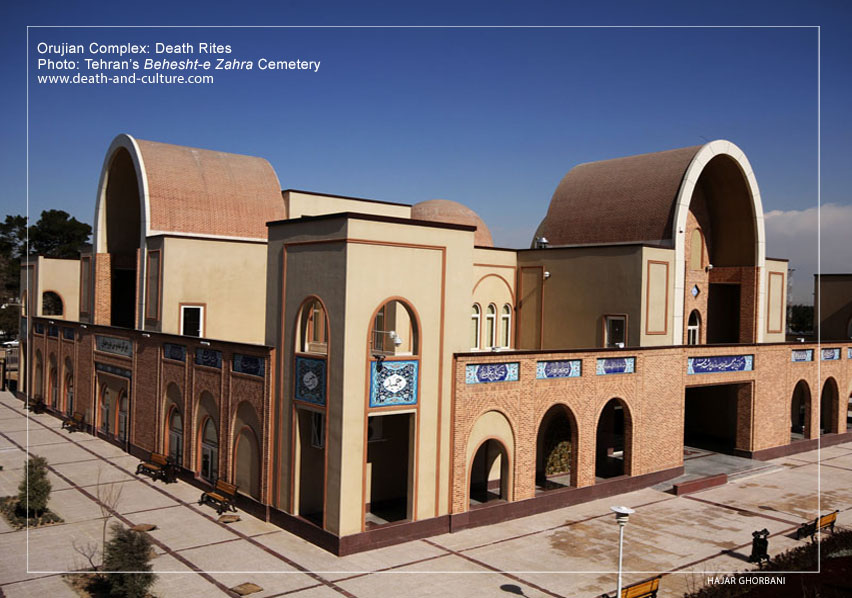

Up until 1991, the cemetery had one building, which was a dedicated ablution (ritual washing and purification) facility. In that year, the Behesht-e Zahra Organization was officially created and a building built using Iranian and Islamic architectural motifs to house the morgue, ablution facility, reception, registration, banking and other bureaucratic offices. Although Behesht-e Zahra is officially run by the City of Tehran, it was forced to become financially self-sufficient in 1993 with revenues generated through fees for burial services as well as the sale of family mausoleums and multi-level graves, surcharges for burials in the older parcels, and renting out commercial space for flower shops, headstone shops, and other related services (Behesht-e Zahra, undated).

As a result of the above developments, the Behesht-e Zahra Organization has expanded rapidly, creating various bureaucratic arms to cope with a variety of tasks from the daily handling of bodies, to ongoing maintenance, event planning for special occasions (prime among them the anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s death every June), human resources management, and long term strategic planning. Here we will focus only on the professionalization and bureaucratization of the funeral rituals, that is the handling of the body from when it arrives at the cemetery until it

has been buried, including corpse washing, wrapping, prayers, graveside rites, and burial.

For buying the whole article please click: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-18826-9_7 or receiving it directly please email me: hghorba1@ualberta.ca